“Markhor: The Majestic Mountain Goat of the Himalayas”

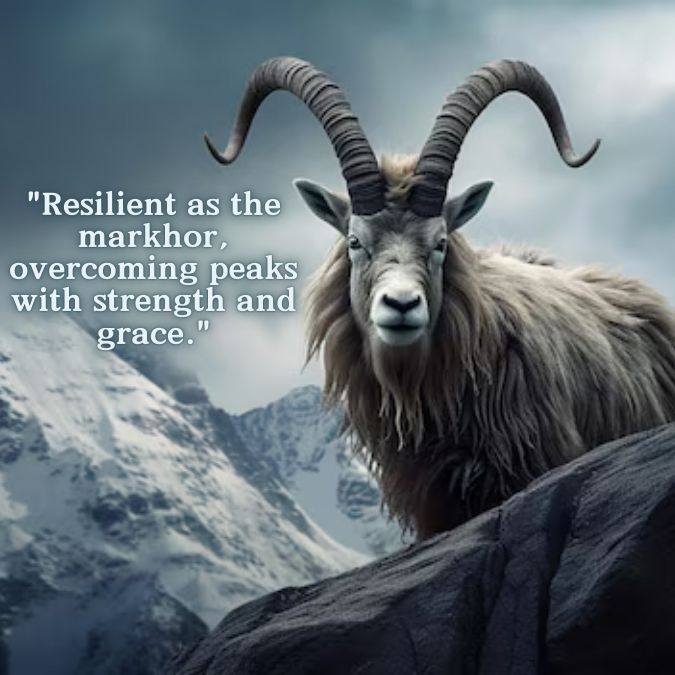

he Markhor (scientific name: Capra falconeri) is a species of wild goat found primarily in the rugged mountainous regions of Central Asia, including parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and India. Known for its remarkable ability to survive in harsh, high-altitude environments, the markhor is not only one of the most awe-inspiring creatures of the mountains, but it also holds cultural, ecological, and symbolic significance. Its majestic appearance and impressive spiraled horns make it a living emblem of resilience, strength, and beauty in the natural world. This article will explore the fascinating characteristics of the markhor, its habitat, conservation status, and its role as a national symbol.

Physical Features and Habitat

The markhor is a large wild goat characterized by its distinctive, corkscrew-shaped horns that can grow up to 1.5 meters long in males. These horns are a defining feature, especially in adult males, whose horns spiral outward in a striking manner that is visually captivating. The females have smaller, less pronounced horns. The markhor’s coat is dense and shaggy, adapted to the cold, rocky, and barren landscapes it inhabits. During winter, the fur becomes longer and thicker, providing insulation against freezing temperatures.

Markhors are well adapted to life in the mountains, particularly in the Himalayas and Hindu Kush ranges. They are typically found at altitudes of 1,500 to 3,600 meters above sea level, where the steep slopes and rocky terrain offer the perfect setting for their agile climbing abilities. Markhors are excellent climbers, capable of navigating narrow, steep cliff faces with ease, which helps them escape from predators and seek out food in the form of grasses, shrubs, and tree leaves.

Ecological Role and Behavior

Markhors are herbivores, and their diet mainly consists of grass, shrubs, and leaves, although they occasionally consume tree bark. They play a crucial role in the ecosystems they inhabit, helping to maintain the balance of vegetation and the overall health of their mountain habitats. By browsing on different plant species, they help prevent certain plants from becoming overly dominant and allow for greater biodiversity in the area.

Socially, markhors are typically seen in small herds, often led by a dominant male, especially during the mating season. Outside of the breeding season, males and females usually live separately, with males either living alone or in bachelor groups. These goats are relatively solitary and are often active during the early morning and late afternoon, which helps them avoid the heat of the midday sun.

Conservation Status and Threats

Despite their adaptability to harsh environments, the markhor has been classified as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Their population has significantly decreased due to a variety of threats. Habitat loss, often caused by human encroachment, logging, and agricultural activities, is one of the primary threats to markhor populations. As more land is cleared for farming or urbanization, markhor habitats are fragmented, making it harder for the species to find adequate shelter and food.

Poaching has been another critical issue for the markhor. The goat’s unique horns are highly prized by hunters, and illegal hunting has significantly reduced their numbers in some areas. Additionally, hunting for sport and for meat remains a problem despite regulations that prohibit such activities in certain regions.

Furthermore, competition with livestock for food resources and grazing land also affects markhor populations, as domesticated animals often outcompete them for access to limited resources. Climate change, which is causing shifts in the habitats of many species, could also pose a future threat to the markhor, altering the availability of food and suitable shelter in the high-altitude regions they call home.

Conservation Efforts

In recent decades, concerted efforts have been made to protect and conserve the markhor population. Conservation programs, particularly in Pakistan, have yielded some positive results. The Markhor is the national animal of Pakistan, and its protection has been taken seriously by the government and conservation organizations. In fact, Pakistan has successfully implemented community-based conservation programs, where local communities are involved in the protection of markhors and other wildlife. These programs have helped reduce poaching and promote sustainable practices that benefit both the local people and the wildlife.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Markhor mating season occurs in the autumn (usually between November and December), and it is marked by intense competition between males. Males engage in head-butting contests to establish dominance and win the right to mate with females. These contests can be violent and involve impressive displays of strength as males charge at each other with their large, spiraled horns. The victor gains access to a harem of females, while the loser is relegated to the outskirts of the group or forced to live alone.

After mating, female markhors give birth to a single kid (young markhor) after a gestation period of around 150 to 170 days. The young are born in the spring and are typically weaned by the age of six months. The markhor’s young are precocial, meaning they are born with their eyes open and are able to stand and walk shortly after birth. However, they remain closely guarded by the mother until they are old enough to join the rest of the herd.

The Markhor as a National Symbol

In Pakistan, the markhor holds immense cultural and national significance. As the country’s national animal, the markhor is a symbol of strength, resilience, and beauty. Its status as a national symbol has contributed to efforts to raise awareness about the importance of its conservation. The image of the markhor, with its majestic horns and rugged appearance, embodies the spirit of the mountains and the perseverance required to thrive in such challenging environments.

The markhor also plays a role in the country’s tourism and eco-tourism sectors. Local communities have begun to see the economic value in protecting markhors and other wildlife, as eco-tourism brings visitors who are eager to observe these majestic animals in their natural habitats. The presence of markhors in local folklore, art, and literature further enhances their status as an icon of natural beauty.

Conclusion

The markhor is not just a symbol of the Himalayan and Hindu Kush mountains; it is also a reminder of the delicate balance between nature and human activity. As a species that has adapted to survive in some of the most extreme conditions on Earth, the markhor represents resilience and the enduring spirit of wildlife. While the threats to the markhor’s survival remain significant, efforts to protect it have shown that conservation, when combined with community engagement, can make a real difference. With continued commitment to preserving their habitats and reducing the impact of poaching, it is possible that the future of the markhor will be brighter. As a national symbol, the markhor continues to inspire efforts for environmental protection and wildlife conservation, ensuring that future generations will also be able to marvel at this magnificent mountain goat in the wild.